Having had a look at some tools for deploying IoT applications there was one piece of the puzzle that was missing, automation. After all, one of my goals is to be able to deploy updates to my project without really any effort, I want the idea of doing a git push and then it just deploying.

And that brings us to this post, a look at how we can do automated deployments of IoT projects using IoT Edge and Azure Pipelines.

Before we dive in, it’s worth noting that the IoT Edge team have guidance on how to do this on Microsoft Docs already, but it’ll generate you a sample project, which means you’d need to retrofit your project into it. That is what we’ll cover in this post, so I’d advise you to have a skim of the documentation first.

Defining Our Process

As we get started we should look at the process that we’ll go through to build and deploy the project. I’m going to split this into clearly defined Build and Release phases using the YAML Azure Pipelines component for building and then the GUI-based Release for deploying to the Pi. The primary reason I’m going down this route is, at the time of writing, the YAML Releases preview announced at //Build doesn’t support approvals, which is something I want (I’ll explain why later in this post).

Build Phase

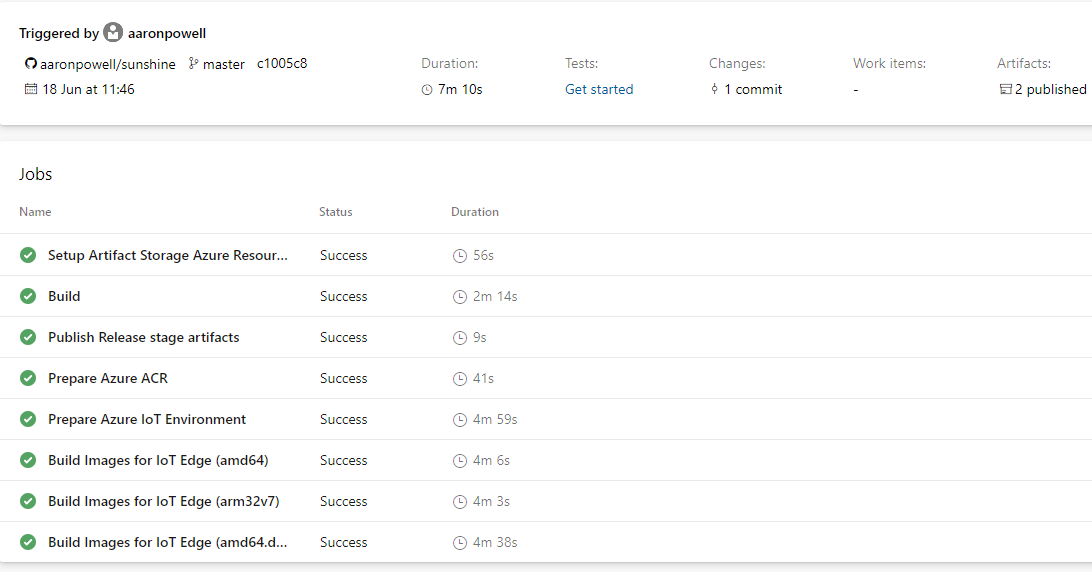

Within the Build phase our pipeline is going to be responsible for compiling the application, generating the IoT Edge deployment templates and creating the Docker images for IoT Edge to use.

I also decided that I wanted to have this phase responsible for preparing some of the Azure infrastructure that I would need using Resource Manager Templates. The goal here was to be able to provision everything 100% from scratch using the pipeline, and so that you, dear reader, could see exactly what is being used.

Release Phase

The Release phase will be triggered by a successful Build phase completion and responsible for creating the IoT Edge deployment and for deploying my Azure Functions to process the data as it comes in.

To do this I created separate “environments” for the Pi and Azure Functions, since I may deploy one and not the other, and also run these in parallel.

Getting The Build On

Let’s take a look at what is required to build the application ready for release. Since I’m using the YAML schema I’ll start with the triggers and variables needed:

| |

I only care about the master branch, so I’m only triggering code on that branch itself and I’m turning off pull request builds, since I don’t want to automatically build and release PR’s (hey, this is my house! 😝). There are a few variables we’ll need, mainly related to the Azure resources that we’ll generate, so let’s define them rather than having magic strings around the place.

Optimising Builds with Jobs

When it comes to running builds in Azure Pipelines it’s important to think about how to do this efficiently. Normally we’ll create a build definition which is a series of sequential tasks that are executed, we compile, package, prepare environments, etc. but this isn’t always the most efficient approach to our build. After all, we want results from our build as fast as we can.

To do this we can use Jobs in Azure Pipelines. A Job is a collection of steps to be undertaken to complete part of our pipeline, and the really nice thing about Jobs is that you can run them in parallel (depending on your licensing, I’ve made my pipeline public meaning I get 10 parallel jobs) and with a pipeline that generates a lot of Docker images, being able to do them in parallel is a great time saver!

Also, with different Jobs you can specify different agent pools, so you can run some of your pipeline on Linux and some of it on Windows. You can even define dependencies between Jobs so that you don’t try and push a Docker image to a container registry before the registry has been created.

With all of this in mind, it’s time to start creating our pipeline.

Building the Application

What’s the simplest thing we need to do in our pipeline? Compile our .NET code, so let’s start there:

| |

The Build job is your standard .NET Core pipeline template, we run the dotnet build using the configuration we define in the variables (defaulted to Release), then do a dotnet publish to generate the deployable bundle and then zip each project as artifacts for the pipeline. The reason I publish all the projects as artifacts, even though the IoT component will be Dockerised, is so I can download and inspect the package in the future if I want to.

Onto creating our IoT Edge deployment packages.

Build IoT Edge Deployment Packages

To create the IoT Edge deployment packages we need to do three things, create the Docker image, push it to a container registry and create our deployment template (which we looked at in the last post).

Creating a Container Registry

But this means we’ll need a container registry to push to. I’m going to use Azure Container Registry (ACR) as it integrates easily from a security standpoint across my pipeline and IoT Hub, but you can use any registry you wish. And since I’m using ACR I need it to exist. You could do this by clicking through the portal, but instead, I want this scripted and part of my git repo so I could rebuild if needed, and for that, we’ll use a Resource Manager template:

| |

Which we can run from the pipeline with this task:

| |

Notice here I’m using the variables defined early on for the -name and -location parameters. This helps me have consistency naming of resources. I’m also putting this into a resource group called $(azureResourceNamePrefix)-shared because if I wanted to have the images used in both production and non-production scenario (which I could be doing if I had more than just my house that I was building against). The last piece to note in the task is that the templateLocation is set to Linked artifact, which tells the task that the file exists on disk at the location defined in csmFile, rather than pulling it from a URL. This caught me out for a while, so remember, if you want to keep your Resource Manager templates in source control and use the version in the clone, set the templateLocation to Linked artifact and set a csmFile path.

When it comes to creating the IoT Edge deployment template I’m going to need some information about the registry that’s just been created, I’ll need the name of the registry and the URL of it. To get those I’ve created some output variables from the template:

| |

But how do we use those? Well initially the task will dump them out as a JSON string in a variable, defined using deploymentOutputs: ResourceGroupDeploymentOutputs, but now we need to unpack that and set the variables we’ll use in other tasks. I do this with a PowerShell script:

| |

Executed with a task:

| |

Now in other tasks I can access CONTAINER_REGISTRY_SERVER as a variable.

Preparing the IoT Edge Deployment

I want to create three Docker images, the ARM32 image which will be deployed to the Raspberry Pi, but also an x64 image for local testing and an x64 image with the debugger components. And this is where our use of Jobs will be highly beneficial, from my testing each of these takes at least 7 minutes to run, so running them in parallel drastically reduces our build time.

To generate the three images I need to execute the same set of tasks three times, so to simplify that process we can use Step Templates (side note, this is where I came across the issue I described here on templates and parameters).

| |

We’ll need a number of bits of information for the tasks within our template, so we’ll start by defining a bunch of parameters. Next, let’s define the Job:

| |

To access a template parameter you need to use ${{ parameters.<parameter name> }}. I’m providing the template with a unique name in the name parameter and then creating a display name using the architecture (AMD64, ARM32, etc.).

Next, the Job defines a few dependencies, the Build and PrepareAzureACR Jobs we’ve seen above and I’ll touch on the PrepareArtifactStorage shortly. Finally, this sets the pool as a Linux VM and converts some parameters to environment variables in the Job.

Let’s start looking at the tasks:

| |

Since the Job that’s running here isn’t on the same agent that did the original build of our .NET application we need to get the files, thankfully we published them as an artifact so it’s just a matter of downloading it and unpacking it into the right location. I’m unpacking it back to where the publish originally happened, because the Job does do a git clone initially (I need that to get the module.json and deployment.template.json for IoT Edge) I may as well pretend as I am using the normal structure.

Code? ✔. Deployment JSON? ✔. Time to use the IoT Edge tools to create some deployment files. Thankfully, there’s an IoT Edge task for Azure Pipelines, and that will do nicely.

| |

The first task will use the deployment.template.json file to build the Docker image for the platform that we’ve specified. As I noted in the last post if you’ll need to have the CONTAINER_REGISTRY_USERNAME, CONTAINER_REGISTRY_PASSWORD and CONTAINER_REGISTRY_SERVER environment variables set so they can be substituted into the template. We get CONTAINER_REGISTRY_SERVER from the parameters passed in (unpacked as a variable) but what about the other two? They are provided by the integration between Azure and Azure Pipelines, so you don’t need to set them explicitly.

Once the image is built we execute the Push module images command on the task which will push the image to our container registry. Since I’m using ACR I need to provide a JSON object which contains the URL for the ACR and the id for it. The id is a little tricky, you need to generate the full resource identifier which means you need to join each segment together, resulting in this $(SUBSCRIPTION_ID)/resourceGroups/${{ parameters.azureResourceNamePrefix }}-shared/providers/Microsoft.ContainerRegistry/registries/$(CONTAINER_REGISTRY_SERVER_NAME) which would become <some guid>/resourceGroups/sunshine-shared/providers/Microsoft.ContainerRegistry/registries/sunshinecr.

Finally, we need to publish our deployment.platform.json file that the Release phase will execute to deploy a release to a device, but there’s something to be careful about here. When the deployment is generated the container registry information is replaced with the credentials needed to talk to the registry. This is so the deployment, when pulled to the device, is able to log into your registry. But there’s a downside to this, you have your credentials stored in a file that needs to be attached to the build. The standard template generated in the docs will attach this as a build artifact, just like our compiled application, and this works really well for most scenarios. There is a downside to this though, anyone who has access to your build artifacts will have access to your container registry credentials, which is something that you may not want. This bit me when I realised that, because my pipeline is public, everyone had access to my container registry credentials! I then quickly deleted that ACR as the credentials were now compromised! 🤦♂️

Securing Deployments

We want to secure the deployment so that our build server isn’t a vector into our infrastructure and that means that we can’t attach the deployment files as build artifacts.

This is where the other dependency on this Job, PrepareArtifactStorage, comes in. Instead of pushing the deployment file as an artifact I push it to an Azure storage account:

| |

This uses a Resource Manager template that just creates the storage account:

| |

And a PowerShell script to get the outputs into variables:

| |

Pushing Artifacts to Storage

Now we can complete our IoT Job by using the storage account as the destination for the artifact:

| |

I’m using the Azure CLI rather than AzCopy because I’m running on a Linux agent. It executes a script that will get the account key from the storage account (so I can write to it), checks if there is a container (script everything, don’t assume!) and then uploads the file into a folder in the storage container that prefixes with the Build.BuildId so I know which artifact to use in the release phase.

Using The Template

The template that I’ve defined for the IoT Job is in a separate file called template.iot-edge.yml, and we’ll need to execute that from our main azure-pipelines.yml file:

| |

We’re relying on the outputs from a few other Jobs, and to access those we use $[dependencies.JobName.outputs['taskName.VARIABLE_NAME']], and then they are passed into the template for usage (remember to assign them to template variables or they won’t unpack).

Creating Our Azure Environment

There’s only one thing left to do in the build phase, prepare the Azure environment that we’ll need. Again we’ll use a Resource Manager template to do that, but I won’t embed it in the blog post as it’s over 400 lines, instead, you can find it here.

When creating the IoT Hub resource with the template you can provision the routing like so:

| |

We can even build up the connection string to Event Hub authorization rules using the listKeys function combined with resourceId. A note with using resourceId, when you’re joining the segments together you don’t need the / separator except for the resource type, which is a bit confusing when you create a resource name like "name": "[concat(variables('EventHubsName'), '/live-list/', variables('IotHubName'))]", which does contain the /.

A new Job is created for this template:

| |

And now you might be wondering “Why is the step to create the production environment in Azure done in a Build phase, not Release phase?”, which is a pretty valid question to ask, after all, if I did have multiple environments, why wouldn’t I do the Azure setup as part of the release to that environment?

Well, the primary reason I took this approach is that I wanted to avoid having to push the Resource Manager template from the Build to Release phase. Since the Build phase does the git clone and the Release phase does not I would have had to attach the template as an artifact. Additionally, I want to use some of the variables in both phases, but you can’t share variables between Build and Release, which does still pose a problem with the environment setup, I need the name of the Azure Functions and IoT Hub resources.

To get those I write the output of the Resource Manager deployment to a file that is attached as an artifact:

| |

Using this PowerShell script:

| |

🎉 Build phase completed! You can find the complete Azure Pipeline YAML file in GitHub.

Deploying Releases

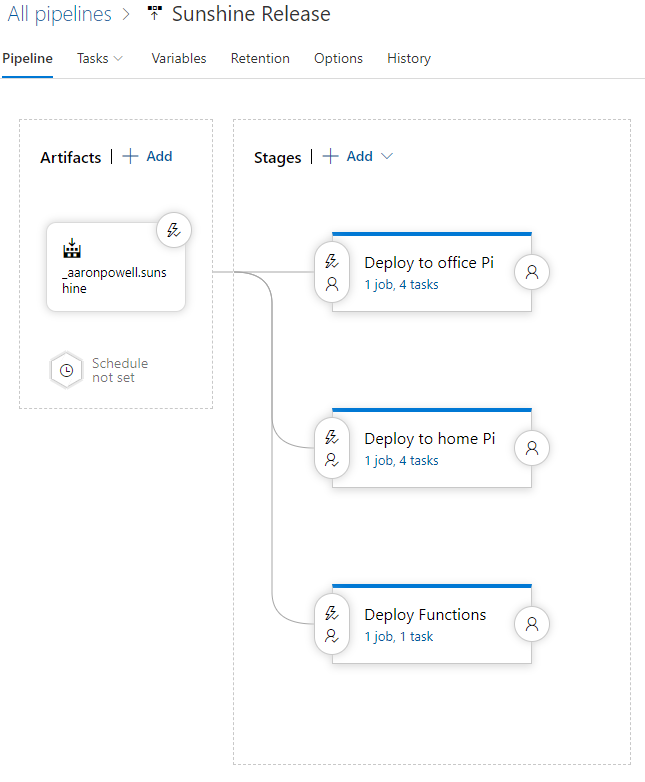

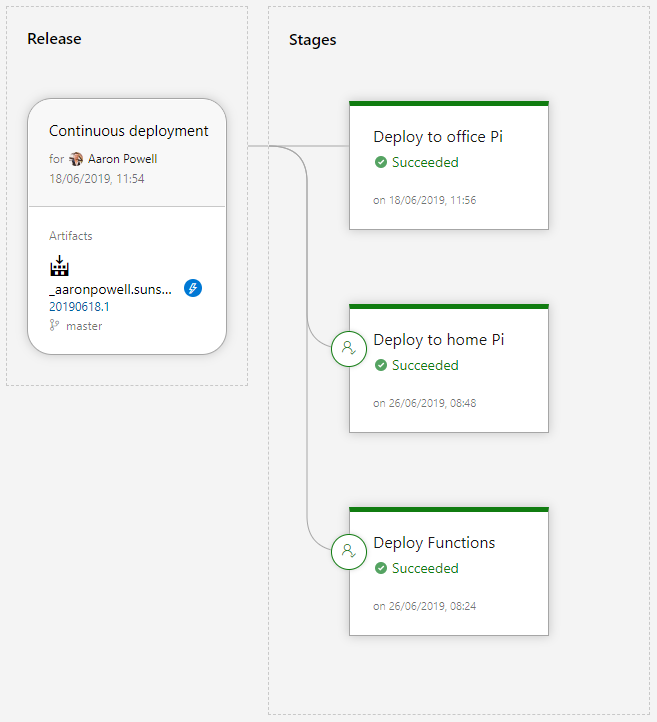

Here’s the design of our Release process that we’re going to go ahead and create using the Azure Pipelines UI:

On the left is the artifacts that will be available to the Release, it’s linked to the Build pipeline we just created and it’s set to automatically run when a build completes successfully.

I’ve defined three Stages, which represent groups of tasks I will run. I like to think of Stages like environments, so I have an environment for my Raspberry Pi and an environment for my Azure Functions (I do have a 2nd Raspberry Pi environment, but that’s my test device that lives in the office, and I just use to smoke test IoT Edge, generally it’s not even turned on).

Pi Stage

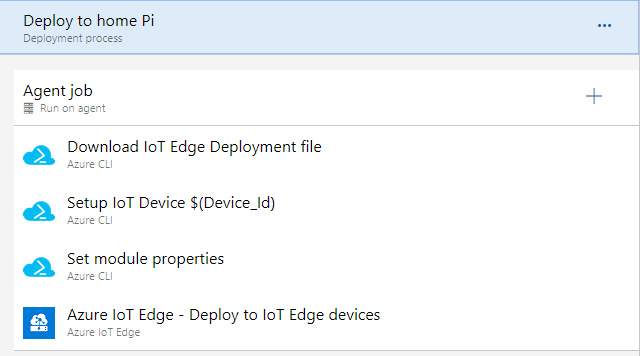

Let’s have a look at the stage for deploying to a Raspberry Pi, or really, any IoT device supported by IoT Edge:

The first task is to get our deployment template. Because I’m using an Azure storage account to store this I use the Azure CLI to download the file, but if you’re using it as an artifact from the build output, you’d probably skip that step (since artifacts are automatically downloaded).

With the deployment downloaded it’s time to talk to Azure IoT Hub!

Provisioning the Device

Continuing on our approach to assume nothing exists we’ll run a task that checks for the device identity in IoT Hub and if it doesn’t exist, create it.

| |

It’s a little bit hacked my shell script skills are not that great! 🤣

We’ll need the name of the IoT Hub that was created using Resource Manager in the build phase, which we can pull using jq. After that install the IoT Hub CLI extension, since the commands we’ll need don’t ship in the box.

The command that’s of interest to us is az iot hub device-identity show which will get the device identity information or return a non-zero exit code if the device doesn’t exist. Since the default of the command is to write to standard out and the output contains the device keys, we’ll redirect that to /dev/null as I don’t actually need the output, I just need the exit code. If you do need the output then I’d assign it to a variable instead.

If the device doesn’t exist (non-zero exit code, tested with if [ $? -ne 0 ]) you can use az iot hub device-identity create. Be sure to pass --edge-enabled so that the device can be connected with IoT Edge!

The last thing the script will do is export the connection string if the connection string can be retrieved (not 100% sure on the need for this, it was just in the template!).

Preparing the Module Twin

In my post about the data downloader I mentioned that I would use module twins to get the credentials for my solar inverter API, rather than embedding them.

To get those into the module twin we’ll use the Azure CLI again:

| |

Using the az iot hub module-twin update command we can set the properties.desired section of the twin (this just happens to be where I put them, but you can create your own nodes in the twin properties). Like the last task the output is redirected to /dev/null so that the updated twin definition, which is returned, doesn’t get written to our log file. After all, our secrets wouldn’t be secret if they are dumped to logs!

It’s Time to Deploy

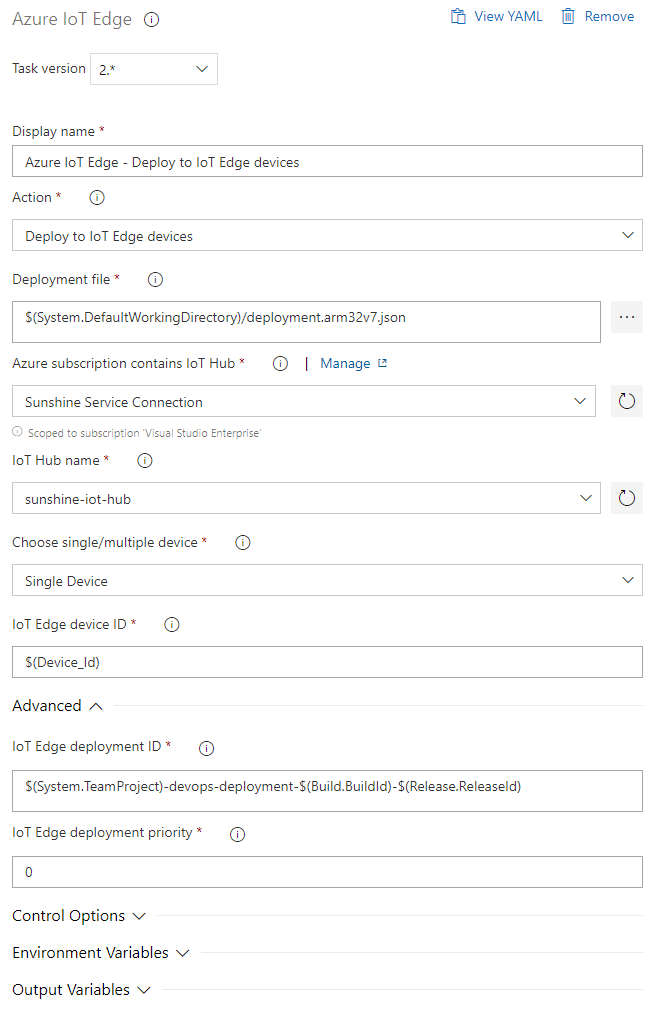

Finally it’s time to send our deployment to IoT Edge! We’ll use the IoT Edge task again, but this time the action will be Deploy to IoT Edge devices:

We specify the deployment template that we’ll execute (the one we got from storage) and it’s going to be a Single Device deployment (if you were deploying to a fleet of devices then you’d change that and specify some way to find the group of devices to target). Under the hood, this task will execute the iotedgedev tool with the right commands and will result in our deployment going to IoT Edge and eventually our device! 🎉

Deploying Functions

With our stage defined for IoT devices it’s time for the Azure Functions. As it turns out, Azure Pipelines is really good at doing this kind of deployment, there’s a task that we can use and all we need to do is provide it with the ZIP that contains the functions (which comes from our artifacts).

There’s no need to provide the connection strings, that was set up in the Resource Manager template!

🎉 Release phase complete!

Conclusion

Phew, that was a long post, but we’ve covered a lot! Our deployment has run end-to-end, from a git push that triggers the build to creating an Azure environment, compiling our application to building Docker images, setting up devices in IoT Hub and eventually deploying to them.

I’ve made the Azure Pipeline I use public so you can have a look at what it does, you’ll find the Build phase here and the Release phase here.

As I said at the start, I’d encourage you to have a read of the information on Microsoft Docs to get an overview of what the process would be and then use this article as a way to supplement how everything works.

Happy DevOps’ing!