Since I converted my blog to a static website whenever posts were shared on social media, which I automatically do via my RSS feed, you’d see something like this in your timeline.

It looked no better in Slack.

Now sure, I’m a handsome guy and that is a great photo if I do say so myself, but do you really need a massive picture of me to adorn a timeline? After all, it doesn’t do much to relate back to the post in question does it?

So when I decided to embark on the rebuilt of my website recently this was one of the things I wanted to fix was that.

Open Graph Protocol

Before looking into how I do things better let’s just look at what we’re working with. When you share links on social sites such as Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, etc. they will look for some additional metadata on the page called the Open Graph Protocol. This protocol started its life in Facebook as a way to embed more information into the social graph that they generate around anything shared on the platform, but over time it’s become a bit of a defacto standard in social graph markup so other sites have adopted it.

Specifically the image comes from the <meta property="og:image" content="..." /> meta property, and there are a number of other meta properties that are useful to markup the social graph.

So when a link is shared the service will request the HTML, look for this metadata and if it exists, embed it in a “card” to make your link more appealing (at least, in theory).

A Better Open Graph Image

In my original theme the og:image was hard coded so that every page used the same image file, which I’m sure was fine for how the theme author intended the theme to be used, but in my usage of it, it was sub-optimal.

I’ve been spending quite a bit of time on DEV this past year and one thing I like about it is that when you share a link there’s a really nice og:image.

You can also optionally upload an image to be the “cover image” which will become the og:image so it doesn’t use the generated card but something you can control.

I decided that I wanted to try and replicate this, allow for me to control the og:image and if there isn’t one, generate a title card like DEV does.

Dynamic Static Images

Everything I need for my website lives in the git repo, including all images. This does mean that the repo is getting larger over time as I blog more and add more rich media to the posts, so I wanted to be careful about how I added these new og:image images. I also didn’t want to make the build pipeline more complex, I think my GitHub Actions process is really quite slick, so I decided that I’d make an API endpoint to generate the images for me, or return a previously generated one, so let’s take a look at how to do that.

Generating Images in .NET

I decided I’d create an Azure Function in F# to handle this problem and to generate the images I’d use the open source ImageSharp library (I’ve used the 1.0.0-beta0009 and 1.0.0-beta0007 packages which are the latest across a few of the dependencies I needed at the time of writing).

ImageSharp is a very low-level image manipulation library and can be used to work with existing images allowing you to edit, crop, transform, etc. but in this post we’re going to create the image entirely via code as it gives us the flexibility to tweak it over time.

Building Our Function

Let’s start by defining a HTTP Trigger Function and combine it with a Blob input binding that will give access to the previously generated image (if there is one). The HTTP binding will have an ID for the post we’re generating the image for:

| |

With the scaffolding in place, let’s start building our image generator!

Limiting Abuse

We’re creating an unsecured API endpoint that allows people to provide a bit of data to via a GET request which will generate an image that is stored in storage. This doesn’t sound like the kind of thing that could be abused does it… Since the og:image URL needs to be unsecured we needed to think of a creative way to validate that what is being requested is actually for a post on my blog. But since it’s all markdown files in GitHub how can we validate that?

It turns out that that isn’t too hard thanks to the work done to create my search app. For this to work we generate a JSON file that is deployed as part of my website (although it doesn’t need to be anymore, but I’m just too lazy to exclude it), so my website has a list of all posts in JSON (there also exists a list in XML which is the RSS output that could be used instead) and that’s what we can use to validate against.

Also, the advantage of having this “database” available is that we don’t need to pass anything more than an ID to the post in the API call, since all the metadata is in the JSON file anyway.

We’ll use the JSON Type Provider to create a strongly typed way of accessing the blog posts. In a new file called RequestValidator.fs we’ll create the module:

| |

A string represents the structure of the JSON (so the Type Provider knows what types to generate) and then two functions are exposed from the module, getBlogMetadata which downloads the JSON using the Type Provider to give us the object graph and tryFindPost which will return an Option when matching the blog by the provided ID.

Time to incorporate this into the Function:

| |

Since getBlogMetadata is an async function we have wrapped the function in an async computation expression and used let! to invoke the method. But the Functions host doesn’t understand the F# async API so we have to convert it back to a Task, and that’s done with Async.StartAsTask. Once the metadata is downloaded it’s converted into the object structure we expect and our tryFindPost method is called with a match expression to either go does a happy path Some post or an unhappy path None, with the latter to be used when the API is being called by someone trying to be tricky. Lastly, we have to cast the result to a common base type, which IActionResult is ideal for, as F# doesn’t do implicit casting, so we have to ensure that every return is returning the same type.

Checking Image Cache

We don’t want to generate the images every time, it’d be much more preferable to only generate the images once and then future requests can use that image. This is where the Blob input binding comes in. To use this binding we need to provide it with:

- The name of the Blob to bind to (

title-cards/{id}.png)- This can use a binding expression that’s shared with the Trigger action, so in this case we can use the ID that comes in on the HTTP trigger on the Blob binding

- Access Mode, in our case we need it to be

FileAccess.ReadWrite - The name of the connection string

- This is optional, it’ll use the storage account of the Function if not provided

This is then bound to a type of ICloudBlob which gives us an API to query information about the Blob as well as grab a copy or upload to it, think of it as a proxy container.

Since the Blob might not exist though we need to check that first, and if it does, send it in the response, otherwise we’ll generate a new image.

| |

On line 19 we use ExistsAsync on the ICloudBlob to see if the blob we’ve requested from storage exists already and if it does the downloadImage function creates a new MemoryStream that the ICloudBlob will be streamed into using the DownloadToStringAsync function so that we can return the stream in the FileStreamResult on line 24 (on line 5 we reset the stream position to 0 so the response can read it). If it doesn’t exist, we’ll need to create the image using ImageSharp.

Creating Our Image

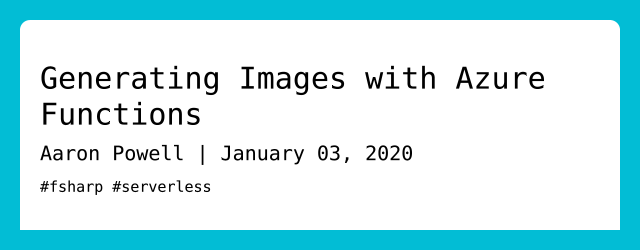

We’ve made a request for an image but it turns on that it doesn’t exist yet, guess we’d better try and generate one, but how do we go about doing that? First, we need to think about what the image we want to generate looks like. Let’s look back at the DEV image we want to replicate:

It’s a rectangle with rounded corners top left and right, a drop shadow, the title of the post with the author’s name below in slightly smaller font and some other little images. I’m going to ditch the avatar of myself (useful on DEV since many people blog, but not on my site) and I’m going to ditch the icons since I’m lazy.

Drawing A Box With Rounded Corners

Seems like a pretty straight forward requirement, draw a box with two rounded corners, but of course it wont be that simple. To do this with ImageSharp we’ll use the SixLabors.Shapes NuGet package (1.0.0-beta0009 version at the time of writing) as it gives us some primitives to work with such as RectangularPolygon and EllipsePolygon.

The reason that we’ll need these two types is that a box with rounded corners isn’t a primitive shape, those are rectangles (or squares if the height and width match), ellipse (or a circle if the height and width match), lines, triangles, things like that. This means we’ll need to get tricky and layer a few shapes on top of each other.

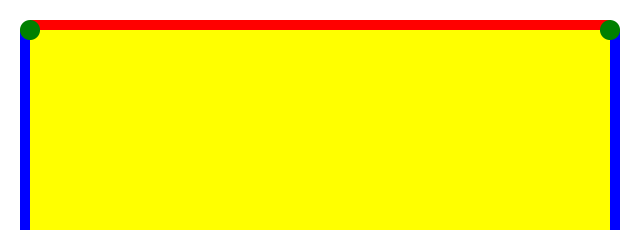

This image shows what we’re going to have to create and I’ve coloured each of the main components. In our solution we’ll colour them the same, but this helps understand the problem.

Let’s create a new file called ImageCreator.fs and start scaffolding out how we’ll make the box (I’ll omit the open statements for brevity):

| |

There’s a lot of arguments to this function, some of them are self explanatory (width, height, colour) and then there’s some like image which is the drawing canvas from ImageSharp.

Now we can draw what I call the “inner box”, which is the yellow one from the image above, and this is skinnier than the full box by the radius of the rounded corner.

| |

With ImageSharp we use a Mutate function on the Image object which we provide a function that takes a IImageProcessingContext (called ctx in the above snippet) that we can manipulate the image from. Because ImageSharp is designed for C# it’s a bit clunky to work with in F# due to the chained API and that F# does implicit returns not explicit like C#, so we’ll use a lot of |> ignore pipes.

From the ctx we will call Fill and provide GraphicsOptions (which we can control the antialiasing of the image) and the colour, then we can start to draw on the canvas with something, in this case, a RectangularPolygon. For the generated image let’s set a 20px gutter around it, so we start the rectangle at the coordinates 30x 30y so that we can have a 10px rounded corner that sits above this box. This is because if the box started at the same x/y as the rounded corner you’d see the corner of the box poking through underneath, so it has to have a slight offset. If you wanted a more dynamic corner sizing then you might pass in the radius of the circle and calculate the x/y offset. Next we need the height and width of the rectangle; height is simple, it’s the total canvas height (height) less our gutter (20px) less the y starting position (30px), so height - gutter - yStart; width is similar, except we also need to subtract the corner radius, so it is width - xStart - gutter - cornerRadius.

Congratulations, you’ve drawn a rectangle!

Now it’s time to add our rounded corners, which we’ll do by creating some circles.

| |

We’re now using EllipsePolygon to generate a an ellipse with an equal width and height to make it a circle not an oval, and we’ll do it twice, one for each corner. We provide an x & y position for the centre of the ellipse, rather than the top-left corner like a rectangle, so that width and height can be appropriately applied. For our left corner we’ll use the same xStart and yStart to draw outwards from and then specify the height and width is double the radius, since these values represent the diameter. With the circles drawn our image will look like this:

Awesome! Now all we need to do is fill in the gaps between the circles and the inner box then everything should be set!

| |

Using the RectangularPolygon struct again we just manipulate some starting positions to fill in the three gaps with a rectangle the width (or height) of cornerRadius.

🎉 We now have a box with rounded corners that looks like it is a single shape but is really made up of a bunch of smaller ones. A point to note is that you can simplify this a bit further by removing the left & right “fillers” and expanding the width of the inner box, but I found that doing so made it a lot harder to track how everything was drawn and positioned, so I’ll take the few extra CPU cycles as the cost of maintainability.

Adding a Drop Shadow

It wouldn’t be modern web design if we didn’t have a drop shadow to make everything pop and the simplest way for us to do a drop shadow of the box is to draw a second box at a slight offset that represents the shadow effect. Now in reality the shadow is drawn first on the canvas since we’re layering everything over the top of it. Let’s expand our generateBox function to have two more arguments that represents the offset of the shadow relative to the main box. Again this won’t be the most efficient solution as we’re going to be drawing a shadow for parts that aren’t visible, but again it’s a small cost of CPU cycles to make it more maintainable.

| |

Here we have a liberal sprinkling of the offset values to shift the box right and down as that’s the direction we’re going with the shadow (assuming a positive offset is passed in, negative will go up and left).

Generating Text

The final thing we need to do with our image is write the text that we want on it. We’ll be putting the title as the main heading and then a subheading that is the author name, published date and the tags. To generate the text we’ll use the SixLabors.Shapes.Text (version 1.0.0-beta0009 at the time of writing) and SixLabors.ImageSharp.Drawing (version 1.0.0-beta0007 at the time of writing) NuGet packages.

Disclaimer: I struggled a lot with doing text properly and while I have a working solution, I’m not sure if it’s the most efficient. I primarily modeled it off this sample so if there’s a better way to do it, please let me know.

Let’s add another function to ImageCreator.fs:

| |

The first thing we need to do to render some text is to choose a font to render it using. For portability I’m going to pick a font off the host machine rather than trying to create one and we can do that with the SystemFont.Find method that the library provides. One thing to be aware of if you work across multiple OSes your available fonts will vary, I got caught out with this because I dev on Linux (via WSL2) but deployed to a Windows-hosted Azure Function, so the fonts were different!

| |

To handle this OS-variation I use a function that checks the OS I’m on and gives me a different font name so I can find the right font family and from that create a Font object with the right fontSize.

Now we need to generate a path which the text will be rendered along, this took a bit for me to understand but once I realised the point I realised how powerful it is. With ImageSharp each character in the string of text is a separate glyph that can be rendered and you can control where that goes relative to what’s preceded it. This makes it easy to have text follow a non-linear path (such as circular text) making complex text generation really easy. To do this we use a PathBuilder from SixLabors.Shapes and add points for shapes to appear on.

But we just need a straight path for the text to follow so we only need a single step in our path that goes through to nearly the edge of the image:

| |

On line 11 we set where the first glyph will appear to be double the gutter width, so we end up with a consistent gap from the edges. Next we’ll add a line to be followed starting from the x position of the origin and a provided y position that will then run through to the right as far as we let it (the passed in xEnd value) with a consistent y. This results in a nice straight horizontal line for the text to follow. Finally we generate a path from the PathBuilder.

| |

We need to create some options to control how the text is drawn onto the canvas (we’ll provide it to the Fill method eventually). First is the TextGraphicsOptions which is similar to the GraphicsOptions we used for shapes, but it has some text-specific properties, namely when to wrap. You might notice the mutable keyword on the let binding. This is because F# objects are immutable by default but we have to set some properties after construction (the same goes for RenderOptions).

With the TextGraphicsOptions created we can create the RendererOptions and copy some of the properties across. RendererOptions is used to control how the glyphs are created from the string of text so we provide it with the font we want to use and the DPI for the font.

| |

With the options ready we can generate the glyphs along the path using the RendererOptions and then mutate the image to render out the text. But we’ve got a compilation error. It turns out that TextGraphicsOptions doesn’t inherit from GraphicsOptions, instead it relies on a custom explicit operator to convert. Well that’s annoying as F# doesn’t have a built-in way to handle the explicit casting like C#, instead you can call the op_Explicit function from the declaring type, or use a little snippet:

| |

Here we’re defining a custom operator, !>, that will handle the explicit cast for us (I don’t claim credit for it, credit to StackOverflow). We also disable the complier warning #77 which tells us to be careful about using op_Explicit as the compiler can do some optimisations with it, but it’ll be fine!

Bringing It All Together

With our two core functions created it’s time to wire everything up and plug it into the Azure Function we started with. Since we’ll have to call each function a few times let’s create a helper makeImage function to get our Image<Rgba32> instance:

| |

This function will take all the information it requires so it’s not tied to our parsing of the blog data. When creating the Image<Rgba32> we provide it a width and height, but they are defined as a float32 (since that’s mostly what we need them as) so they are boxed as int for the constructor (this is so ImageSharp can work with sub-pixel graphics but the final image is to a whole pixel).

Up until now the background has been transparent, but let’s give it a colour to help it pop:

| |

And finally we’ll call generateBox and addText

| |

Since all these methods return the Image<Rgba32> we can leverage F#’s pipeline operator to pass everything through in a nice pipeline. You’ll also see that when we call addText we start with the y position being half the height of the image (title is vertically aligned in the middle) and then increase the offset from that for the other lines of text so it doesn’t overlap.

The resulting output is an image like so:

All that is left now is to return that from the Azure Function.

Connecting With Our Function

| |

We unpack the metadata from our post (title and tags) then call our makeImage function that returns us the Image<Rgba32> object. Since we know that it doesn’t already exist in storage we’ll write it back by converting it to a stream:

| |

And using the ICloudBlob UploadFromStreamAsync function to write it. Once we reset the stream position it can be handed over to FileStreamResult and the client will get the image.

Conclusion

I hope you’ve enjoyed this look at how we can generate and store images using Azure Functions and ImageSharp. If you’re looking at how to manipulate an existing image check out this tutorial which also uses ImageSharp.

But we were looking at the primitives, how to create the base shapes, overlap them appropriately and then draw some text across them.

We also saw how to combine the HTTP trigger with a Blob input binding so that we get a connection to our blobs setup without us needing to do a lot of the wire-up ourselves. If you want to see the complete solution you’ll find it on my GitHub.

We didn’t cover how to deploy to Azure, but there’s plenty of docs already on that. I’m using GitHub Actions for this project, you’ll find them here.

And if you have any advice on how to improve the image generation let me know!