A little over a year ago I wrote about dissecting some phishing attempts and while I still got the odd one here and there, nothing really was slipping through the M365 spam filters.

Until yesterday that is. Over the last 24 hours I’ve gotten around a dozen phishing attempts to one of the sub-addresses on my domain, and given that there was so many I figured I’d take a look at them.

Taking it apart

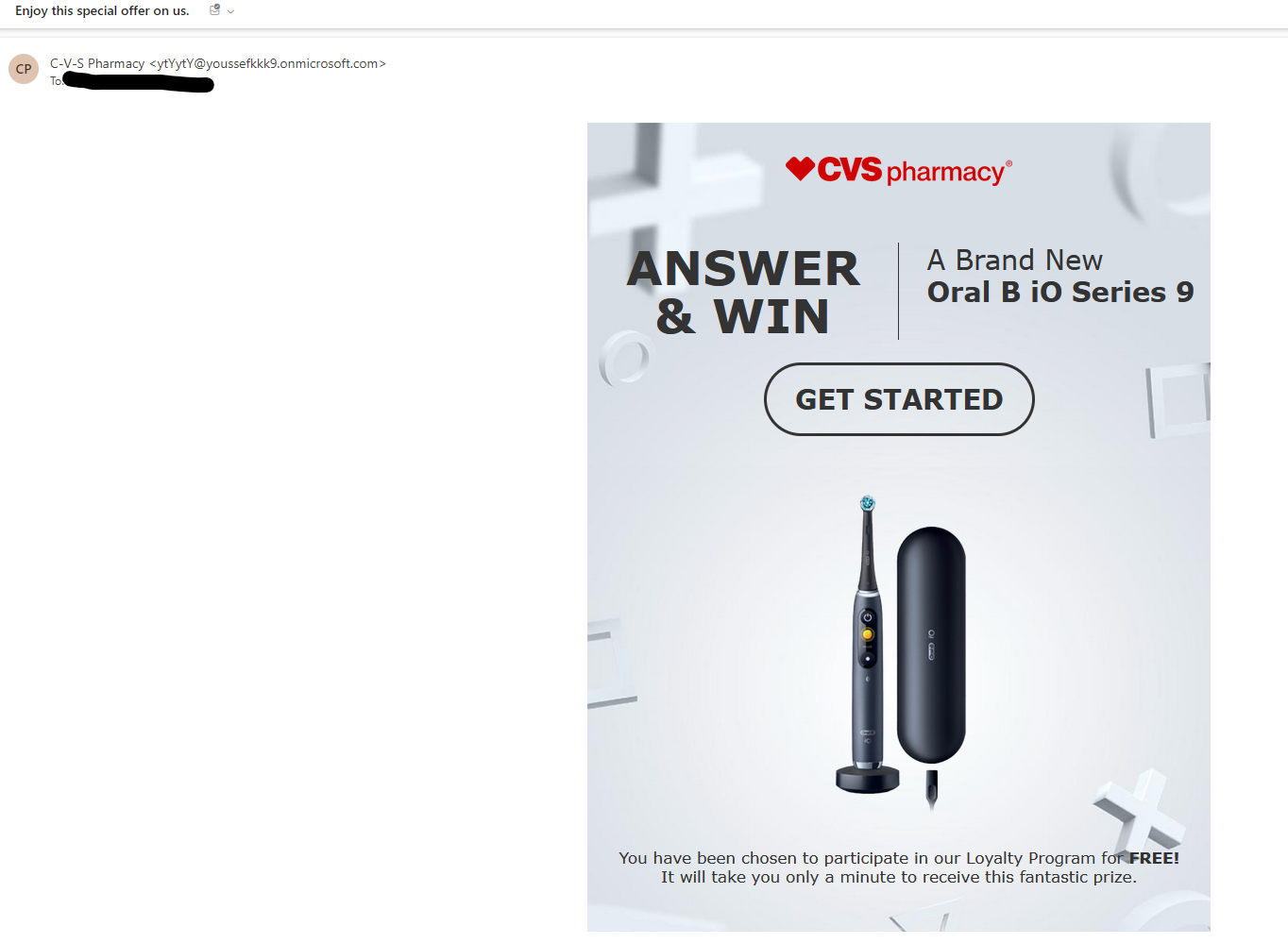

The first thing I noticed about this one is that it had gotten through my spam filter, and when I opened the email I could see why, the email wasn’t a text-with-image email, it was a HTML email with a single image in it.

Since that is just a large image in the email body, and with no alt-text, there’s nothing for the spam filter to scan for, without it doing OCR. Also, it’s surprisingly lacking in spelling mistakes, which are a really easy way to catch these things. It is worth noting that the image wasn’t displayed initially, I had to tell Outlook to allow the image to be displayed for an untrusted email address.

Where to next

Unlike the last ones which had you download a HTML file and then it was all done locally, this linked me off to an external website. Here’s the address http://allallaossn.lat/cl/5394_d/6/72997/137/35/77720 although you probably shouldn’t click on it, unless you want to go digging yourself. The address bounced through a few other locations, presumably setting some cookies or capturing other bits of info about me, and then it landed me here:

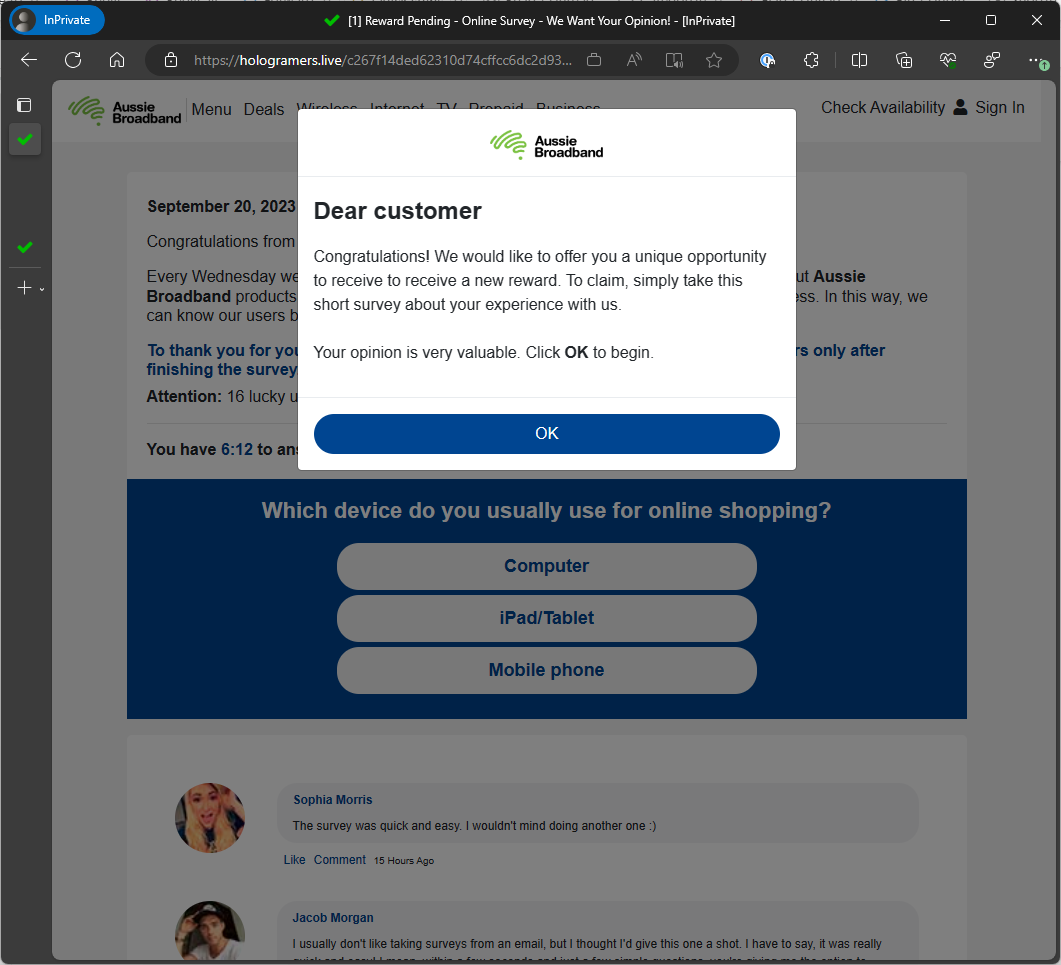

Interestingly enough when I opened it in Chrome I ended up at a different page with a different survey pipeline:

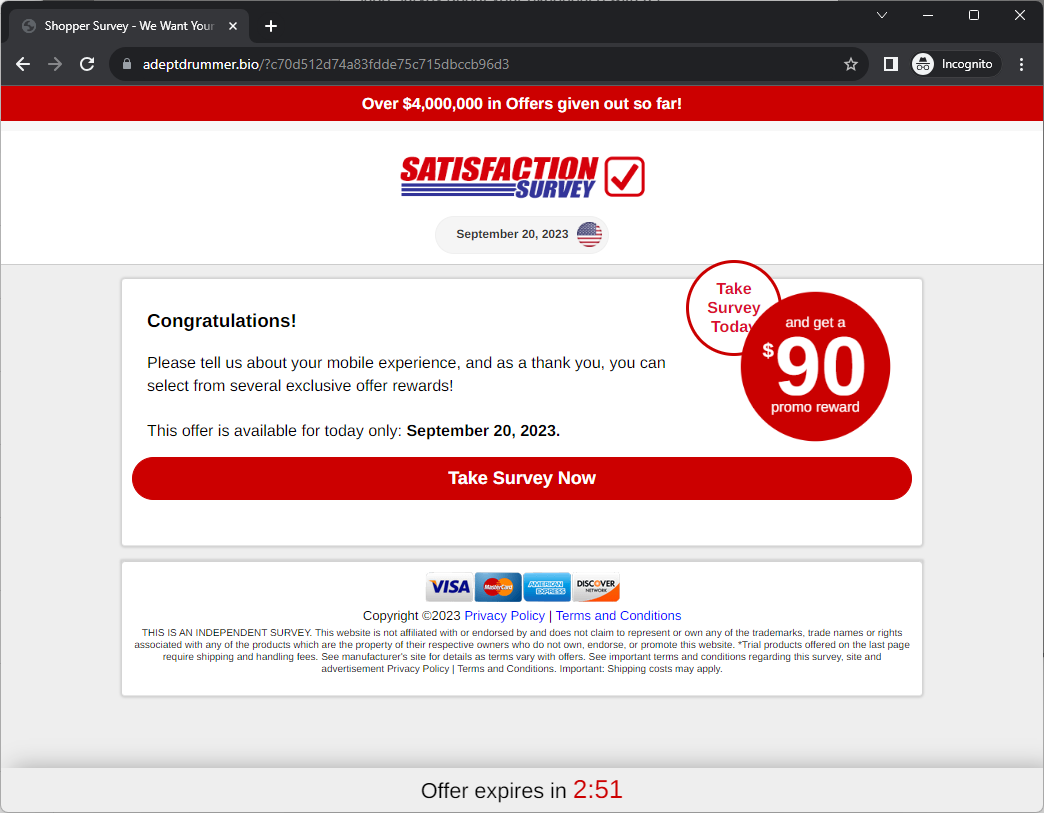

I’m going to stick with dissecting the Edge version, as that’s what I started with. It’s also worth noting that while I expected this to be a standard phishing attempt, it’s actually a survey scam, which is a little different. The goal of this is to get you to complete a survey, and then you get a prize. The prize could be a lot of different things (we’ll see my prizes later on), but the goal of this scam is to get you to subscribe to a paid service that is really hard to get out of.

The page make up

I opened up the source of the page and it turned out that it doesn’t really contain any HTML, just some JavaScript includes. You’ll find a gist of the source if you want to play along.

I expected that it’d work similar to the local file ones I looked at last time, and that turned out to be correct. There’s a huge string of text and some obfuscated functions in the code. This is the most interesting part (formatted for readability):

| |

What’s it doing?

We’ll notice the array, _0xc50e which starts it off and it’s essentially acting as a utility for the rest of the code, as those are the relevant pieces of info to make up a string.

The function _0xe23c is then invoked several times to decode HTML chunks to then generate the HTML that goes into the page, and this works by looking at parts of _0xc50e and then using that to decode the string that was passed into it. Let’s take it line by line:

| |

Admittedly this isn’t that readable, but lets deobfuscate it. _0xc50e[2] is the string 0123456789abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ+/ and then it’s calling split on it, which will split it into an array of characters. So g is now an array of characters.

| |

There, that’s readable. Next up:

| |

This is a bit more interesting, it’s calling slice on the array, which will return a new array with the elements from the start index to the end index. So h is now an array of characters from the start of 0 to the value of e. When debugging, the first time through e was 6, so we ended up as an array of the first 6 characters of the string, which are the numbers 0 to 5. The next line is similar, just with a different end point in the string.

We then come to this lovely bit of code:

| |

Let’s deobfuscate it and look at what it’s doing now:

| |

So it’s taking the string that was passed in, splitting it into an array of characters, reversing that array and then reducing it. The reduce function is then looking at each character in the array and if it’s in the h array (which is the first 6 characters of the string) then it’s adding the index of that character in the h array multiplied by e to the accumulator. The accumulator is initialised to 0 so the first time through it’ll be 0 + 0 * 6 which is 0. The next time through it’ll be 0 + 1 * 6 which is 6. The next time through it’ll be 6 + 2 * 6 which is 18. And so on.

Finally, we have our loop and return value:

| |

Deobfuscation won’t help much, the magic variables point to '' within the array, creating a starting string. We then loop around while using remainder operator to jump through i and find a number to return. This number is then used by the calling function to look up character in another array which is decoded elsewhere as a character code to then get the string character. Here’s a calling function:

| |

And it was receiving a huge string like ZQvZvxZZQvZxZQvZZxZZZZZxZZQZvxZQvvQxZZQvQxZZZZQxZvZvxZZZvQxZZZQZxZZ (only with 50k characters in it), and the values 89,"QZvxOrGpf",4,3,35, which is then used to decode the string.

Ultimately, it generated the html you’ll find in generated-html.html of the attached gist. The page actually runs this sort of code 3 more times, but with different keys. Inspecting the other ones showed that they were doing output that was injecting JavaScript into the page using eval (which is how the stuff was executed at the end of the decoding). Here’s the output I found:

| |

I was a little disappointed that I didn’t have the element matching $('.pb-cheers') anywhere on the page to get congratulated as I progressed through the survey. Poor form phishers, if you’re going to have code to cheer me on, at least use it! (also, it’s weird that 50% doesn’t write to txt but to a different variable that isn’t used anywhere else)

Taking the survey

Naturally, the next thing I had to do was actually take the survey. Clicking each option would result in this function being called:

| |

The args being passed in is a reference to which answer you’ve selected, which came back from the server in the AJAX call (and shout-out to jQuery for still being around, this reminds me of years gone by 😜). The request doesn’t contain anything much of interest:

bid: 393074817

fnp: c267f14ded62310d74cffcc6dc2d9395

sid: 39

lid: 1

cmp: Aussie

cnt: 14

qid: 26

aid: 649

step: 1

pos: false

What I can gather is that the fnp is the unique tracking ID for me and cmp is the “campaign” they are pretending to be (Aussie is my broadband provider). The value of bid seems static across sessions too, so I’d assume it’s just another part of their tracking.

And here’s a sample response back:

| |

I’ve got to admit, there’s quite a lot of data in the response, sure, it’s mostly null, but that’s a large property set and none of the responses ever populated them. I guess there’s a variety of flows that could use this backend and they just return the same data structure for all of them, adjusting the data in the response as needed.

The questions that you go through are pretty standard, it’s the illusion of profiling you through age, shopping habits, gender (which in this one only had Male and Female, but the one Chrome got had Male, Female and Other - yay for inclusion?), etc. but interestingly enough there was no real data capture like name, email, the stuff you’d expect they are really after.

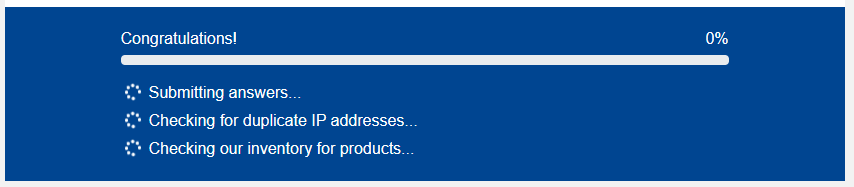

Once the survey was completed I was told my details were being checked:

Shockingly, the progress bar and “checks” aren’t doing anything:

| |

I really admire the staggered setTimeout calls, because if something caused one of them to error or run longer, you could end up with things out of order! 🤣

It is making another server call at the same time, which gets the HTML for the prizes, but it also doesn’t wait for the checks to finish before rendering the HTML, so depending on the network connection you can see the prizes before the checks are done, or the checks can be done and dismissed well before the prizes are rendered.

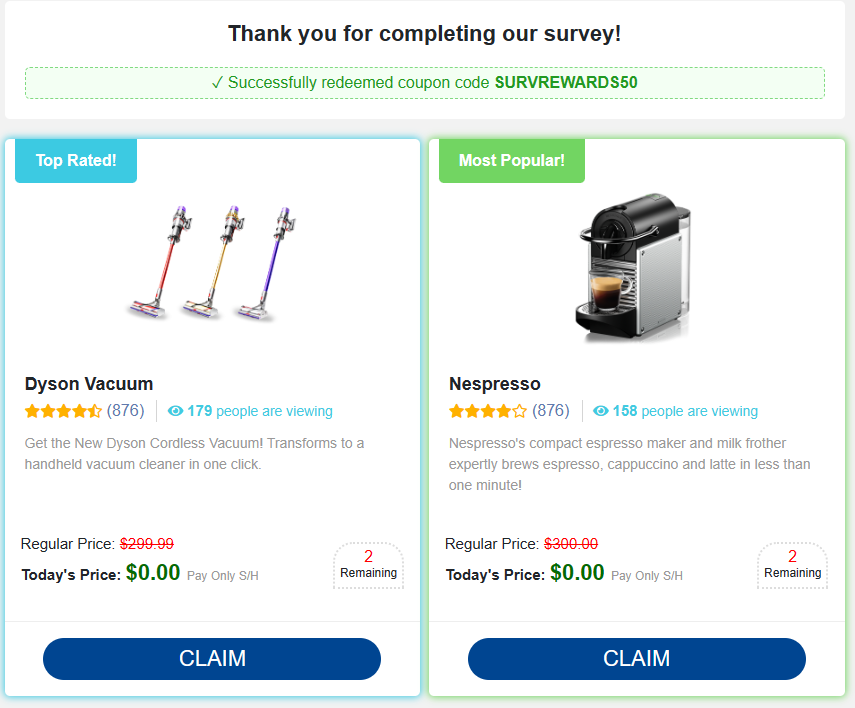

Anyway, here’s what I “won”:

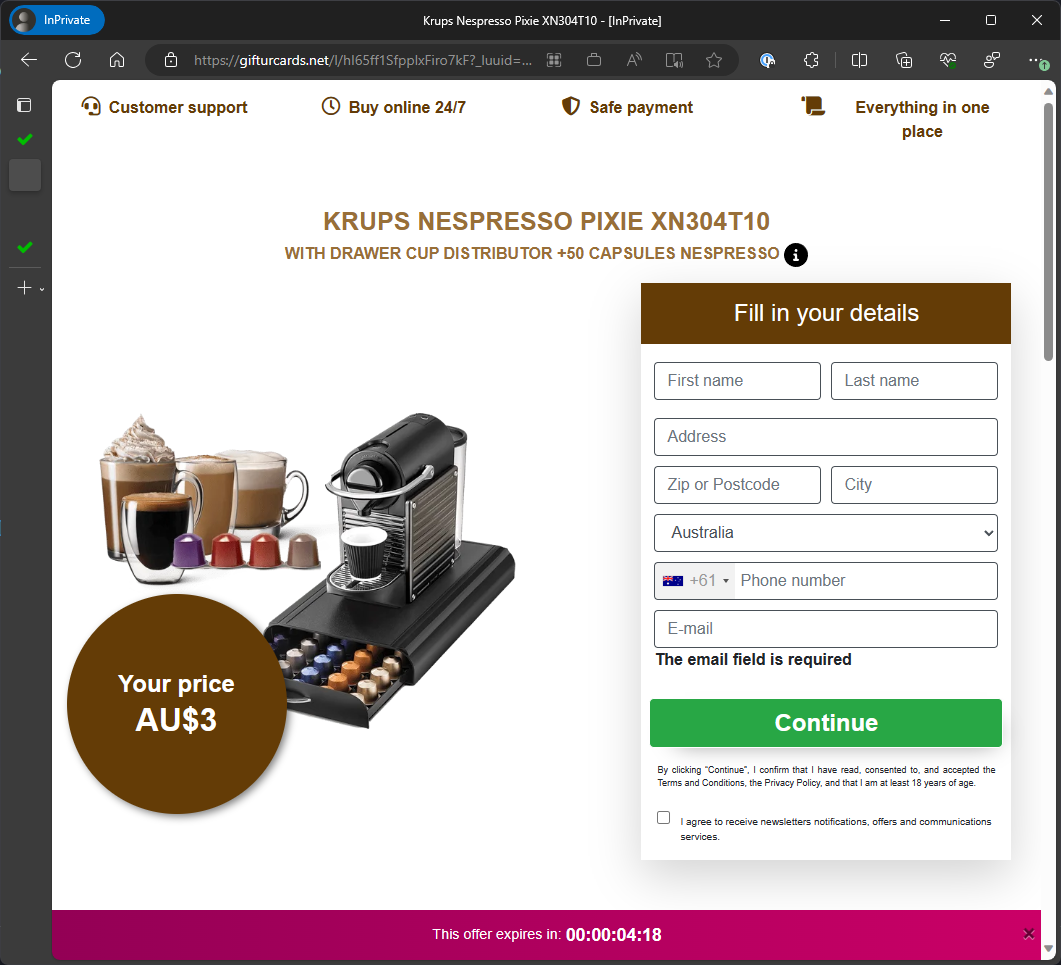

Clicking these links sent me off to another site, https://gifturcards.net/l/hI65ff1SfppIxFiro7kF?_luuid=988bf154-bb2b-4606-b300-14c6a07c53ae for example (again, remember that this is a scam site) where they are finally doing some data capture!

I didn’t dig too much into the prize site as it’s pretty clear how the scam is going to go from here, and looking at the code it’s not doing anything that isn’t overly obvious, there’s a form, it captures your info and moves yo along to get more info until you hand over a credit card and you’re subscribed to something that you probably won’t get out of with ease.

Wrapping up

I find it fascinating the level of complexity in the obfuscation that is used to create a page like this, the fact that there was multiple cyphers in the page and the decoding of the code to result in the HTML or JS that was injected was really quite complex.

Anyway, that was a fun way to spend a few hours!